Why Psychological Safety Means Everything for Your Business

Read Time: 9 minutes

Read Time: 9 minutesCreating an environment of openness, candor, and humility can help your business in surprising ways. See why psychological safety keeps showing up again and again in teams that succeed.

The single worst aviation disaster in history actually occurred on the ground. In March of 1977, a KLM 747 smashed into the side of a Pan Am 747 on a runway in Tenerife. Claiming 583 lives, it is the deadliest plane crash in history—a tragic record that still stands nearly 50 years later.

A slew of factors contributed to the event—dense fog, limited airport experience with large jets, a nearby terrorist attack, pressure to stay on schedule, confusion, and, predominantly, miscommunication.

But investigation into the crash turned up a chilling theory: The disaster might have been avoided if the KLM flight engineer had been more assertive in voicing his valid concern that the runway wasn’t clear. So what stopped him?

When Wrong Hypotheses Go Right: An Introduction to Team Psychological Safety

Research on cockpit crews surged in the 1980s, and researchers unexpectedly uncovered intriguing insights into team effectiveness. NASA researcher H. Clayton Foushee conducted a study about the effects of fatigue on cockpit crews, expecting to see a correlation between fatigue and increased error rates. To Foushee’s surprise, the fatigued crews that had recently flown together for several days outperformed their fresh-on-the-job counterparts. While the tired crew members made more individual mistakes, the team compensated—having flown multiple flights together, they were more adept at catching and correcting one another’s errors. In contrast, the well-rested crews, unfamiliar with each other, didn’t achieve the same level of teamwork.

These results caught the attention of Harvard doctoral student Amy Edmondson when she was looking for a similar pattern in medication error rates among hospital teams. Her expectation was that better teams would have fewer errors. After a six-month study, Edmondson was dumbfounded by her results. The data pointed in the opposite direction: better teams were reporting more errors than less effective teams. Edmondson relates, “Mistakes happen—the only real question is whether we catch, admit, and correct them. Maybe the good teams, I suddenly thought, don’t make more mistakes, maybe they report more.”

Edmondson broadened her study to account for this new thought, and the results were conclusive. Teams that are made up of members that feel safe to speak up about issues are more effective at their work. She went on to publish a groundbreaking paper and coined the term “psychological safety”—a shared belief held by members of a team that it’s safe to take risks, express ideas and concerns, ask questions, and admit mistakes, all without fear of negative consequences. As Edmondson put it, “it’s felt permission for candor.”

Why Psychological Safety Is Important

This “permission for candor” was not felt by KLM flight engineer Willem Schreuder in Tenerife. At the time, a flight engineer was considered something of a “ship’s mechanic.” Schreuder was vital to maintaining systems and troubleshooting mechanical problems, but he didn’t carry the prestige and “infallibility” of a captain. The captain he was flying under was none other than Jacob Veldhuyzen van Zanten–head of KLM's flight training department, KLM’s chief flight instructor for all Boeing 747s, and the face of their most recent advertising campaign.

We know from cockpit voice recordings that shortly before the crash, Schreuder heard something from the ATC tower that made him think another plane was on the runway in front of them. Fog limited visibility, and there was radio interference between planes and the tower. Veldhuyzen van Zanten was antsy to take off, even interrupting the first officer’s flight clearance readback to ATC with “We’re going!” As the KLM plane began its takeoff roll, Schreuder asked, “Is it not clear, that Pan American [plane]?” Veldhuyzen responded emphatically that they were clear, and continued without pause. Moments later, they collided.

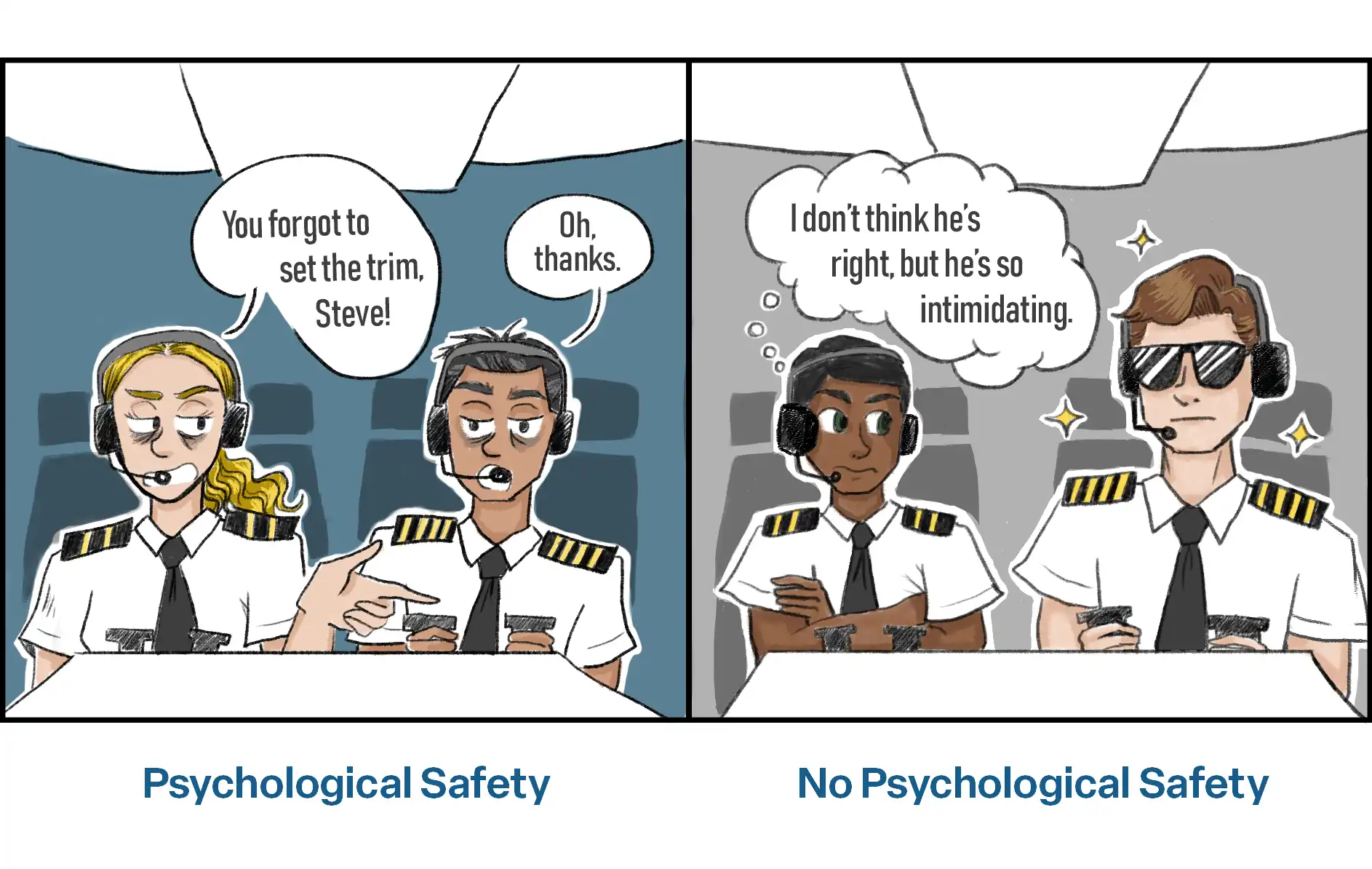

Schreuder’s behavior tells us much about the culture of that team. He was clearly concerned that the Pan Am plane hadn’t cleared the runway, but when his question about it was abruptly shut down, he didn’t push back.

Recorded comments from other cockpits at Tenerife reveal that Veldhuyzen van Zanten sounded “anxious” and “in a hurry.” This tension was no doubt felt in his cockpit. But because Veldhuyzen van Zanten held rank in the company, Schreuder deferred to him. Even though Schreuder had more flight hours under his belt, he clearly did not feel safe disagreeing with the captain.

In this case, psychological safety was literally a matter of life and death. While most workplace situations don't have such dire consequences, the importance of open communication remains essential in our interconnected, knowledge-driven economy. Real value comes from the ideas and insights people bring to the table. It may seem intuitive that leaders would reward input from everyone, but research shows that many people feel unable to speak up at work. This isn’t a minor issue—it’s a huge missed opportunity. When voices are silenced, fresh ideas and solutions get left on the sidelines, and businesses lose out on all that untapped potential.

Google Discovers Yesterday’s News: Psychological Safety Is a Deal-Maker

Three years after the publication of Edmondson’s work, Google began internal research called Project Aristotle to discover what it takes to make the “perfect team.” They built algorithms to match people with similar life experiences, demographics, and interests. They hired high performers and experienced managers, and gave their employees unlimited resources. They expected to find that “building an effective team would be like solving a puzzle – that the best teams would be those where outstanding individuals were put to work together.” (Italics ours)

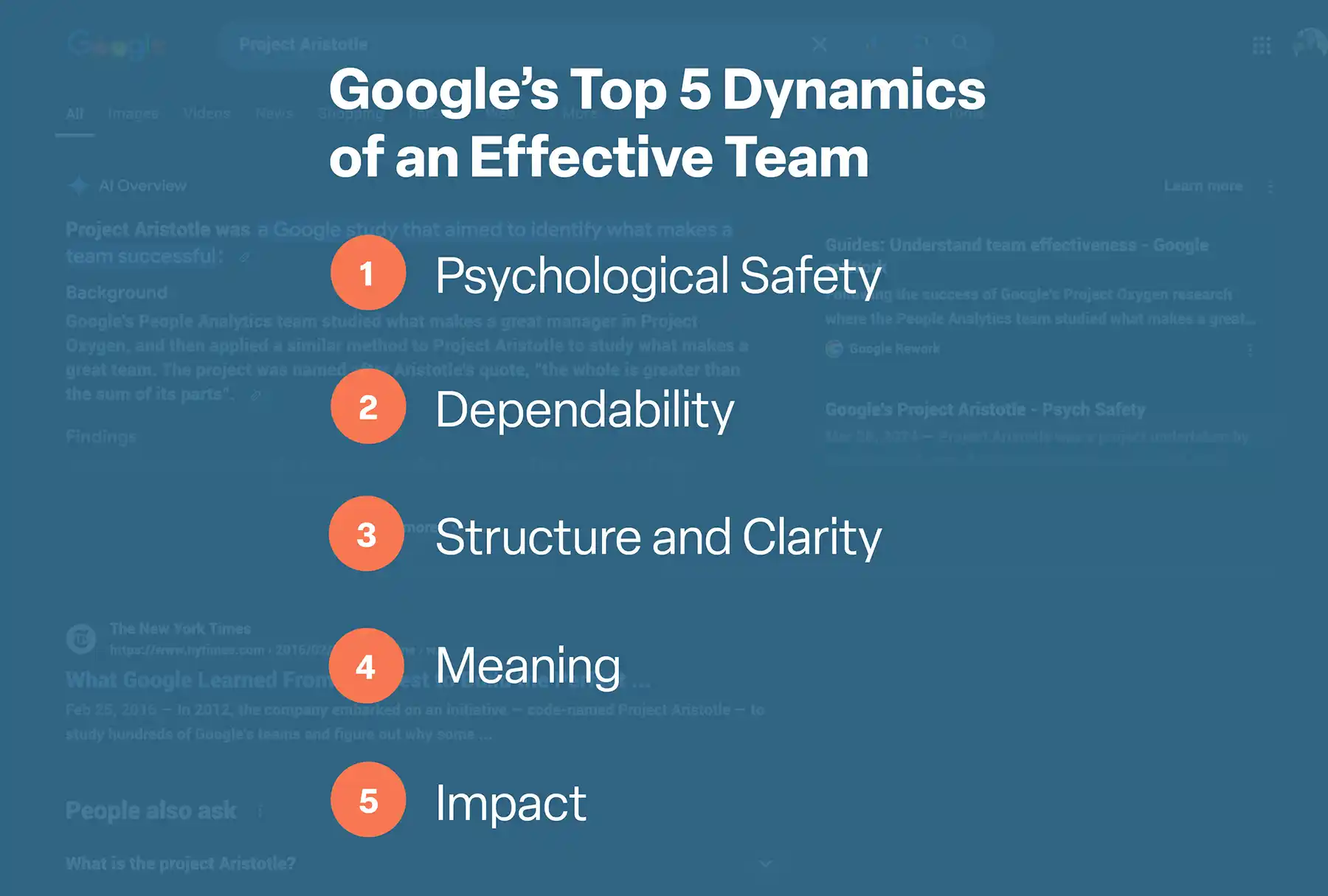

Wrong again. After three years of data crunching, Google found that five dynamics—regardless of the individuals involved—separated top-performing teams from those at the bottom. In fact, the same individual placed on two different teams would perform better on the one that had these dynamics:

- Psychological Safety

- Dependability

- Structure and Clarity

- Meaning

- Impact

Psychological Safety is at the top for a reason—it turned out to be the most important of the five factors. “Our researchers found that the best teams created a climate of openness where team members admit to their errors and discuss them more often…Psychologically safe teams accelerate learning and innovation by acknowledging mistakes and exploring new ideas.

But does psychological safety affect the bottom line? The report continues, “Our research revealed that sales teams with high ratings for psychological safety actually brought in more revenue, exceeding their sales targets by 17%. Teams with low psychological safety fell short by up to 19%.”

Like all good influencers, Google didn’t discover psychological safety, but they certainly popularized it. In the years since Project Aristotle, this concept has gained enormous traction. But applying it is an uphill battle against human nature. So what is it, exactly, that causes people to remain silent when they have something important to say?

We Are All Experts in Impression Management

No one wants to look stupid. No one wants to seem bad at their job or get labeled a know-it-all. So every day, we consciously and subconsciously engage in what psychologists call “impression management.” This is a form of self-presentation that seeks to manage the way others view us.

We’ve all been doing this since we were children because it’s natural and sociable. Unfortunately, some of the beliefs and related behaviors we’ve picked up along the way aren’t always helpful. Don’t want to look stupid? Don’t ask questions. Don’t want to seem incompetent? Don’t admit weaknesses or mistakes. Don’t want to seem negative? Don’t critique the status quo.

These techniques are effective for self-protection, but they rob us and our colleagues of small moments of learning. Innovation cannot exist under these conditions. For work that relies on specialized knowledge to flourish, the workplace must be a safe place to share our knowledge. This means sharing concerns, questions, mistakes, and half-formed ideas, without the fear that we will be punished or humiliated.

In psychologically safe environments, we feel confident that our questions will be valued, our ideas welcomed, and our mistakes openly discussed. Being wrong is not a threat to our reputation, but a part of growth and collaboration. This allows us to focus fully on our work, without stressing over what others might think of us.

Google’s research found that “individuals on teams with higher psychological safety are less likely to leave [their organization], they’re more likely to harness the power of diverse ideas from their teammates, they bring in more revenue, and they’re rated as effective twice as often by executives.” These kinds of benefits are music to the ears of any business leader. So how do you ensure a culture of psychological safety in your organization?

Psychological Safety Starts with Leadership

As a leader or manager, you’ll inevitably face bad news. When a product fails or certain targets are not met, someone has to break that news to you. Your response will set the bar for psychological safety within your organization.

You could respond with comments such as, “Whose fault is this?”, “Don’t bring me problems, bring me solutions!”, or “How do we make sure this never happens again?” These types of responses stifle candid communication and don’t move your problem toward a solution.

Conversely, responding with a simple “What did we learn from this?” opens the floor for critical problem solving, bypasses useless blame-games, and invites constructive criticism. It gets you to your original goal faster.

If you catch yourself asking, “Why didn’t they come to me earlier?”, try reframing it. Instead, ask, “What did I do that made it difficult for them to come to me?”

As a busy person yourself, you may have previously made comments like “Just get it done,” “Not now, I’m too busy,” or “You should know that by now.” Even if unintentional, these statements signal that someone’s voice isn’t welcome. So the next time an issue arises, they’ll be reluctant to come forward.

How to Model Psychological Safety

Psychological safety isn’t just about reacting to bad news. You can proactively build it into your projects from the beginning, and reap all the benefits that science has shown it can offer. Edmondson’s work has revealed three practices that have a major effect on the psychological safety of your team:

- Frame the work as a learning problem, not as an execution problem. Acknowledge uncertainty, encourage interdependence, and emphasize, “We’ve never been here before, so we need each other.”

- Acknowledge your own fallibility. Good leaders stay humble and welcoming: “I may miss something, so I need your input.”

- Model curiosity. Ask open-ended questions to invite everyone’s voice (questions that you genuinely don’t know the answers to).

Build Psychological Safety into Your Teams

The Tenerife Airport Disaster was a terrible event, but it incited positive change throughout the aviation industry. One of the most concrete outcomes was the development of Crew Resource Management (CRM), a training methodology designed to improve psychological safety within flight crews. CRM addresses rigid hierarchies and the fear of speaking up by training captains to invite, actively listen to, and respect input from all crew members. It normalizes discussions about mistakes, fosters open feedback loops, and trains junior members in assertiveness.

CRM has been so successful that other industries, such as healthcare, maritime transport, and even the DoD have adopted its methodologies. In nuclear power plants and other energy sectors, psychological safety has been proven to reduce human error in control rooms. Fire departments and emergency medical services use psychological safety to enhance team coordination in high-pressure situations, and tech companies use psychologically safe retrospectives to identify and address issues in collaborative projects.

These examples prove two things: 1) psychological safety is not automatic, and 2) it can be learned. Putting the effort and resources into developing an environment of psychological safety will be well worth it.

What If Some Team Members Are Not on Board with Psychological Safety?

In a perfect world, everyone would embrace and support psychological safety. Unfortunately, in the real world, some individuals can turn the vibe of a great team into something resembling a tense family dinner. Sometimes, even just one person can poison the air of a previously safe environment. In an upcoming article, we’ll dive into the telltale signs of these psychological safety disruptors and share tips for addressing their behavior.

We are custom software experts that solve.

From growth-stage startups to large corporations, our talented team of experts create lasting results for even the toughest business problems by identifying root issues and strategizing practical solutions. We don’t just build—we build the optimal solution.

From growth-stage startups to large corporations, our talented team of experts create lasting results for even the toughest business problems by identifying root issues and strategizing practical solutions. We don’t just build—we build the optimal solution.